what is it that when a person who has had a stroke says yes to everything

Universal Images Group Editorial/Getty Images

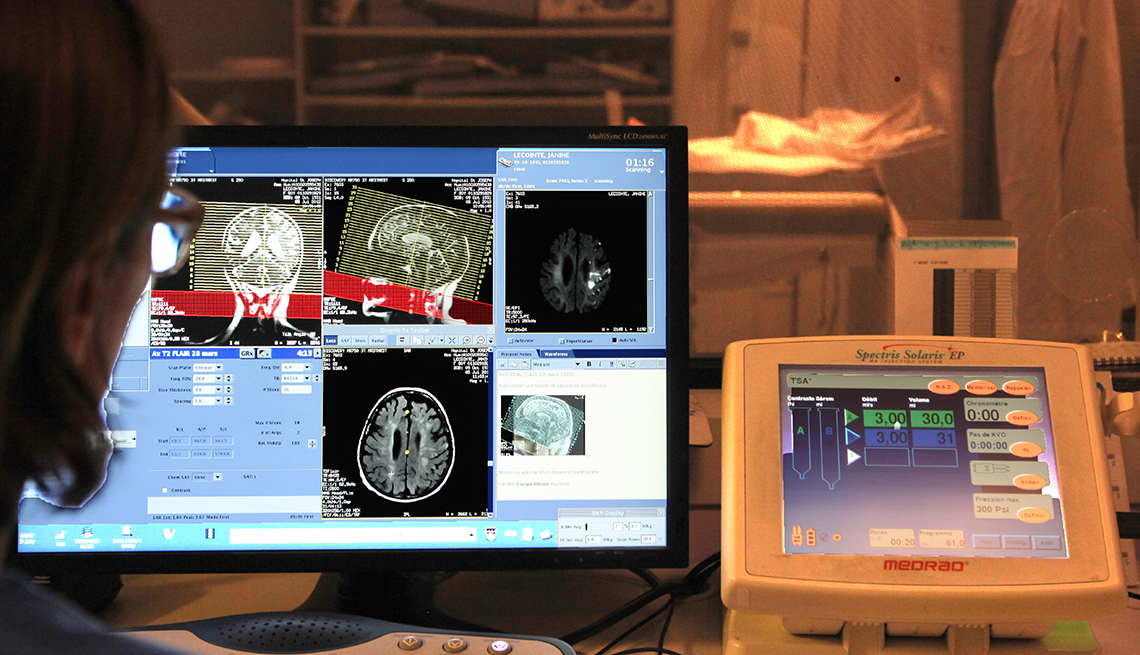

En español | Spotting the alarm signs and early symptoms of a stroke is key to reducing the chance of permanent inability or decease when the disease strikes. Just practice y'all know what to look for?

Frequently, a stroke is mistaken for an upshot that takes place in the heart. Simply it happens in the brain when blood period is disrupted either by a blockage or bleeding. Deprived of the oxygen information technology needs, that office of the encephalon starts to dice.

"If you think about it, the encephalon is really responsible for everything that you do. It's responsible for your power to move, your ability to speak, your ability to call back, your ability to encounter, your ability to feel, to hear, etc. And then really, a loss of any of those things tin can be a sign of a stroke," says Mitchell Elkind, 1000.D., professor of neurology and epidemiology at Columbia University and president-elect of the American Heart Association.

A quick and easy way to remember the most mutual signs of a stroke is with the acronym FAST. It stands for "face drooping, arm weakness, speech difficulty and fourth dimension to call 911." Elkind, notwithstanding, likes to tack on ii additional messages ahead of the acronym: B and E. These stand up for "residuum" and "eyes," since a loss of balance and a sudden change in vision tin also signal a stroke. Severe headache is another warning that shouldn't be disregarded, he says.

COVID-19 and Strokes

As the sum of coronavirus cases continues to climb, experts are learning more than about the virus and the illness information technology causes, called COVID-xix. And an increasing number of reports from hospitals around the globe prove that in some patients, the disease tin lead to stroke. One of the reasons, experts predict, has to do with COVID-19'southward impact on claret clotting. Critical affliction and severe infections likewise predispose patients to stroke.

However, not everyone who has a stroke experiences the hallmark symptoms or is clued into them right abroad. Headache and dizziness, for example, are like shooting fish in a barrel to attribute to everyday triggers such as allergies and stress. Arm weakness? Perhaps it was tweaked at the gym.

"The brain is tricky; neurology is tricky. So these things can sometimes be written off or ignored," Elkind says. "And that'due south why information technology'southward so important to educate people nearly these things, so that [people] don't do that."

Here's what four stroke survivors experienced during the days and minutes leading up to their strokes.

Doug and Karen Tapking

'Oh crap, I'm having a stroke'

Doug Tapking, 77, Draper, Utah

10 years ago, Doug Tapking and his married woman, Karen, were waiting for a tabular array at a steak house in Thou Oaks, California, when Tapkin got a muscle cramp in his left arm. Information technology wasn't his first one that day either. Earlier in the afternoon, the then-66-year-old had a charley horse in his left leg and left arm while packing for an upcoming vacation. He'd also been having severe headaches for days — sinus pressure, he thought.

By the fourth dimension the couple and their friends were seated for dinner, the cramping in Tapking's arm had subsided and conversation turned toward the Tapkings' upcoming cruise trip. That's when his friend, John, started to notice something was off.

"He looks at me at some point and says, 'What's wrong? Stop mumbling; you're mumbling,' " Tapking recalls. "And I don't remember mumbling. Frankly, I thought we were just having a conversation similar we're doing right at present. Then he would ask a question and I would respond. At least I thought I was responding. … And all of a sudden he blurts out, 'Are yous having a stroke?' "

Know the Warning Signs of a Stroke

Interim fast can reduce the chance of harm or death from stoke. Here are the common alert signs to proceed in listen.

B: Balance or coordination may be off.

E: Eyes. Sudden blurred or double vision

F: Face drooping

A: Arm weakness

S: Speech communication difficulty

T:Fourth dimension to telephone call 911

If you experience whatsoever of these symptoms, it's best to call 911, says Mitchell Elkind, M.D., professor of neurology and epidemiology at Columbia University and president-elect of the American Middle Association. Arriving to the hospital in an ambulance ways yous will be seen correct away and your stroke treatment will exist faster.

John proceeded to ask Tapking a serial of questions: whether he could smile, for instance, or heighten his artillery. Tapking, somewhat oblivious to what was happening, played along.

"My right arm came up without whatsoever problem, only my left arm was limp at my side. Then I reached out and I grabbed my left arm at my wrist, you lot know, I kind of pulled it upwardly to my breast level. And I let go of it, and information technology merely barbarous immediately into my lap," he says. "And at that bespeak, I vividly think proverb to myself, Oh crap, I'm having a stroke."

Tapking remembers someone calling 911, just the residuum is pretty much a blur. He later learned that the left side of his confront was drooping, or every bit married woman Karen puts it, looked "totally melted." The paramedics rushed Tapking to the closest infirmary, where doctors correct away diagnosed an ischemic stroke, which results from an obstruction and is the most common blazon of stroke. It turns out a "astringent autopsy" in an avenue in his encephalon was blocking his claret flow.

"Think of a garden hose with multiple layers — a high-force per unit area hose — and a dissection is the internal portion of that hose separating and coming down into the centre of it," thus causing a buildup of claret, Tapking explains.

Doctors broke up the clot that had formed near the dissection and inserted a stent to repair the damaged blood vessel. They besides gave him a clot-busting drug.

Different many stroke survivors, Tapking made a full recovery, with no lasting concrete or mental damage. He credits his friend'southward quick recognition of the stroke and the fast care he received at the hospital for his fortunate outcome. Now an advocate for stroke education and treatment, Tapking urges everyone to know where their closest stroke heart is. He also says if y'all notice something out of the ordinary — be it a design of headaches or a series of cramps — "pay attention to information technology." Your body could be trying to warn you that something is wrong.

Maury Mendenhall

'An explosion in my brain'

Maury Mendenhall, 45, Washington, D.C.

"It was like an explosion in my brain," Maury Mendenhall says about the intense pain she experienced back in May of 2018. The mother of ii had just returned habitation from a piece of work trip to Republic of zimbabwe and Nigeria and was lying in bed, hoping to overcome jet lag and shake a headache that had been building upwards for weeks.

Feeling sick was unusual for Mendenhall, who works on HIV/AIDS projects at the United States Agency for International Evolution (USAID). "I am not the type of person who has headaches often," she says. "But each day, my headaches got a little bit worse, and I remember going to piece of work [earlier in the week] and trying to talk to people and not being able to conspicuously say the things I wanted to say. And in that location wasn't annihilation I could exercise to make [the headaches] ameliorate."

The pain got then intense that morning afterward her trip that Mendenhall burst into tears. Her female parent, who was in town to watch the kids while she was traveling, came upstairs to check on her. "I could barely talk to her at that indicate. But when I saw my mom, I said, 'Help. Big help.' "

They drove to MedStar Washington Hospital Eye, which was five minutes from her firm, and by the time they arrived, Mendenhall couldn't get out of the car "and nothing that I said made whatever sense," she recalls.

Lower Your Stroke Risks

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, upwardly to eighty percent of strokes in the U.South. are preventable through lifestyle changes. Mitchell Elkind, of Columbia University, lays out a few steps you can take to reduce your risk of stroke:

1. Get enough of physical activity — at least 30 minutes a day, five days a week.

2. Eat a good for you diet and limit common salt intake, which can cause a spike in claret pressure.

3. Maintain a salubrious weight.

4. If y'all smoke, quit.

5. Know your cholesterol, claret pressure and blood sugar levels. If they are too loftier, work with your doctor to bring them under control.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed that a tangle of abnormal blood vessels on her brain, called an arteriovenous malformation (AVM), had ruptured, causing a pool of blood on the left side of the brain and a lot of swelling. The doctors had to temporarily remove function of her skull to relieve the pressure.

Recovery was a long and difficult road for Mendenhall, who woke up from the trauma unable to string together a judgement in a way that fabricated sense. She'd too lost the ability to quickly process what others were proverb to her. And learning to read and write again was one of the virtually frustrating and "embarrassing" parts of the process for the former college literature major.

Several months after her stoke — and with a lot of therapy and encouragement from her family and other brain injury survivors she met forth the way — Mendenhall returned to work, albeit with a few accommodations. She at present has a computer that reads to her, for example. She also records meetings so that she can get back and listen to everything that was said as many times as she needs to.

"It's hard not being able to do the things I used to do" with ease, Mendenhall says. "Only I was incredibly lucky."

Joyce Sampson

'Follow your gut'

Joyce Sampson, 64, Silver Jump, Maryland

One morning most 10 years ago, Maryland resident Joyce Sampson was looking for her keys when something strange happened. She opened her mouth to inquire her son to help her, simply she couldn't come with the word key.

"I kept saying, 'Hand me the lamp' or 'hand me the rug' — something like that," Sampson recalls. "I felt like it was unnatural." Sampson somewhen found her keys, despite losing the words, and proceeded to bulldoze herself to the hospital — "which was a mistake," she now admits. Imaging tests revealed she had suffered a stroke in her frontal lobe. It turned out to be her showtime of many.

Over the next several weeks, Sampson, a quondam journalist, experienced a range of strange symptoms that landed her in and out of the hospital. For instance, she recalls hearing a "whoosh" sound, followed by a feeling that the walls were shaking. Her limbs would often get weak, or she would randomly lose her ability to read or write.

She remembers calling her sis and trying to carry on a normal conversation. But from her sister's reaction, the words coming out of Sampson'southward mouth didn't make whatsoever sense. With each apropos symptom, Sampson went to the hospital. And well-nigh every time, doctors diagnosed a stroke. Somewhen, her wellness care team kept her at the hospital for several days to monitor her status. When she stopped having strokes, Sampson was released to rehabilitation, followed by years of therapy to assistance her recover from the repeated injuries to her brain.

Sampson's advice to others? "Follow your gut," she says. The early on alert signs of stroke may not always be textbook or seem obvious. And in today'south fast-paced world, it's easy to write off confusion and disorientation as stress or exhaustion, when really, it could be something much more serious.

Debra Meyerson

'Rebuilding a life'

Debra Meyerson, 62, Menlo Park, California

It started with a funny feeling in her right leg — almost similar she was losing a fleck of muscle control. But Stanford University professor Debra Meyerson figured it was just a cramp "or a nerve thing or something."

Later that solar day while on a hike with her family about Lake Tahoe, the feeling in Meyerson's leg grew worse — so bad, in fact, that they cut the walk short. Then, came the headache. Meyerson took some aspirin before bed and hoped everything would feel better in the morning. Only when she woke up, her head was still throbbing.

Meyerson's married man, Steve Zuckerman, handed her some more medicine. He remembers his married woman "trying to pick information technology up with her right hand," he says, but that "she was having to concentrate unbelievably hard and was barely moving her manus." That'due south when he put 2 and 2 together — the problem with her correct manus and right leg. Zuckerman suspected a stroke.

The couple went to the nearest hospital, where tests showed damage to Meyerson'due south encephalon. It wasn't clear, still, what was causing the harm, then Meyerson was transferred to a larger infirmary about 30 minutes abroad. There, doctors discovered that a dissection (or tear) in her left carotid avenue was blocking the blood flow to her brain, and they suspected it had been there for several months. (This explains some intermittent headaches and disorientation Meyerson experienced weeks earlier her stroke — one incident even landed her in the emergency room, but doctors couldn't find annihilation incorrect. The tear probable moved during those times, slowing blood period to the brain.)

It took until the next morning time for the severity of Meyerson's symptoms to fully fix in: The correct side of her body was paralyzed and she'd lost all speech. Life as she knew it was forever inverse.

Determined to "get back to kind of where she was," Meyerson pushed through iii tough years of rehabilitation before realizing something: She "reluctantly acknowledged that maybe this was a life change and that she was going to take to deal with rebuilding a life with disabilities" instead of just working to limit them, Zuckerman says.

Meyerson, who has aphasia — a side effect of a stroke that can affect the ability to speak or embrace language — had to give up her position as a tenured professor, only she all the same works at Stanford as an adjunct professor, conducting inquiry on the experience of stroke survivors in the rehabilitation process. With her son, Meyerson cowrote a book called Identity Theft: Rediscovering Ourselves After Stroke. She besides founded a nonprofit with Zuckerman called Stroke Frontward, to help survivors and their families rebuild their lives afterwards a stroke.

"Recovery isn't merely about regaining capabilities — that is critically important, and you lot should exercise as much as you lot tin — but a significant percentage of the 800,000 stroke survivors every twelvemonth just merely won't," Zuckerman says. The goal of Stroke Forwards, he explains, "is to try to accomplish every bit many people in this unfortunate situation as possible realize that they shouldn't only talk most recovering capabilities." Because the emotional role of the recovery is but every bit important.

Source: https://www.aarp.org/health/brain-health/info-2020/stroke-survivor-stories.html

0 Response to "what is it that when a person who has had a stroke says yes to everything"

Enregistrer un commentaire